Password Reset

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

8 Minutes

Clinicians must routinely assess liver fibrosis to diagnose and monitor the progression of a variety of liver diseases, including hepatitis, chronic alcohol abuse, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Traditionally, fibrosis has been assessed by liver biopsy, which is invasive and carries risks. Blood tests and imaging tests are minimally invasive and provide an alternative assessment of liver fibrosis. At the UPMC Center for Liver Care, experts leverage non-invasive liver disease assessment daily to improve patient care.

Liver biopsy has traditionally been indicated to assess fibrosis caused by liver disease but causes pain in 84% of patients, as well as bleeding and other complications. Additionally, liver biopsy is inconvenient to both the patient and the health care system due to the cost, time, and resources necessary to perform a biopsy. When successfully performed, liver biopsy specimens are small, representing only 1/50,000 of the liver with considerable sampling variability, and a single sample does not capture the dynamic process of fibrosis. Fortunately, non-invasive methods for liver disease assessment have been developed and are increasingly being validated for a variety of indications. Moreover, in some patients these tests can be ordered and interpreted by physicians who are not liver disease specialists to better determine who would benefit from referral to a specialty center.

There are two types of tests for non-invasive liver disease assessment (NILDA) — blood-based tests and imaging-based tests. Blood-based tests are widely available but not widely used by non-specialists. Imaging tests are more accurate than blood-based methods but require specialized equipment. Nonetheless, most tertiary care centers in North America have the necessary hardware and software for NILDA using imaging.

Blood-based tests for liver disease assessment leverage markers of liver function and other physiologic processes as surrogates of the degree of liver fibrosis. The information needed for the blood-based assessments can be obtained from tests routinely processed by clinical laboratories. These include the prothrombin index, platelet count, and alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels. Extracellular matrix components such as hyaluronate may also be evaluated. The values obtained from the routine laboratory tests are then plugged into formulas proven to reflect the degree of fibrosis present. More than a half dozen blood-based tests have been established, some available commercially and some from academic sources. These include the FibroTest, APRI, FIB-4, NAFLD Fibrosis Score, Hepascore, FIBROSpect II, ELF score, and FibroMeter. I recommend the Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) test, especially to nonspecialists. It has excellent diagnostic power and is widely available, free to use, easy to understand, and well validated1. The FIB-4 test combines standard biochemical assessments — platelet count, ALT, and AST — with patient age in its calculation of liver fibrosis.

Imaging tools for NILDA measure the liver stiffness through elastography, a medical imaging modality that maps the elastic properties and stiffness of soft tissue. As fibrosis progresses, the liver tissue becomes stiffer. There are three major imaging tests based on elastography: transient elastography (TE), magnetic resonance elastography (MRE), and shear-wave elastography (SWE). These three techniques are equally good at diagnosing advanced fibrosis. MRE is superior to TE and SWE in detecting less advanced fibrosis. Additionally, standard ultrasonography can be used to diagnose steatosis – fatty deposits in the liver – and grade steatosis as mild, moderate, or severe. The magnetic resonance imaging technique of quantitating the proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) is also useful in determining the degree of steatosis, as it accurately measures liver fat2.

In our clinic, the UPMC Center for Liver Care, TE is often the first assessment performed in patients with chronic liver disease who need to be staged for fibrosis. TE captures 100X the area sampled in a biopsy and yields immediate results. When we use TE to rule out cirrhosis prior to a treatment or procedure, further tests, such as a biopsy, are typically not necessary. In patients with chronic liver disease, TE is done every six to 12 months to see if the patient’s disease is progressing or regressing.

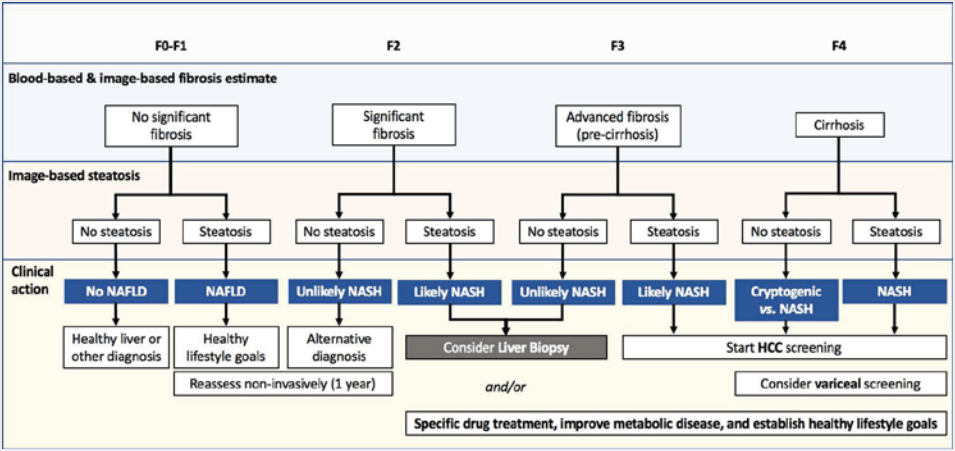

NILDA is particularly useful to ensure that liver biopsies are being performed on the correct patients in accordance with evidence-based recommendations. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Proposed algorithm for fibrosis stratification, screening, and management of patients with liver diseases. MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MASH, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. F0-F4, Fibrosis staging (F0 indicates no fibrosis, F4 is severe, irreversible fibrosis or cirrhosis). From Altamarino et al. Used with permission.

If the only indication for doing a liver biopsy is to stage liver fibrosis, the physician should not do the biopsy. If the NILDA tells you what you need to know, a biopsy is typically unnecessary. Depending on the modality, NILDA has an accuracy of 70%-90%. The more fibrosis present, the more reliable the result. Non-invasive imaging assessments are most accurate when detecting cirrhosis. There will always be some patients who require biopsy after non-invasive assessment, and biopsy may be indicated to assess liver disease etiology, inflammation, or graft rejection.

Portal hypertension is a complication of cirrhosis that negatively impacts prognosis. NILDA can be used to determine if portal hypertension is clinically significant and guide hepatologists after cirrhosis is diagnosed. The non-invasive assessments may allow the hepatologist to determine who will need an endoscopy and who will have a higher risk of liver complications, particularly after surgery. We can also use NILDA to determine which patients should be surveilled for liver cancer.

We recently started performing TE during our yearly clinical follow-up visits with all liver transplant recipients. Doing TE annually promotes early detection of liver disease, whether it is new disease or a recurrence of the liver disease that necessitated the transplant. Non-invasive assessment should have the same utility in liver transplant recipients as has been proven for nontransplanted patients with liver disease. This approach promises to improve patient care and long-term outcomes after liver transplantation.

Noninvasive methods of assessing liver disease may also have utility in assessing livers from extended-criteria donors during organ procurement. In a proof-of-concept study, we found that TE measurements, namely the controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement, may be useful surrogates in assessing liver steatosis and fibrosis prior to organ procurement3. Using MRI-PDFF, we can assess steatosis without obtaining a liver biopsy from a potential donor.4 In a study of 143 living-liver donors, we found that donors who met other criteria for donation with no or mild steatosis (less than 20%) detected by MRI-PDFF experienced favorable postsurgical outcomes, including liver regeneration. Thanks to this technology, very few living donors undergo biopsy prior to liver donation at UPMC.

Widespread adoption of blood-based liver disease assessments has the potential to improve health care utilization. Blood-based tests, such as the FIB-4, are widely available, and the studies supporting their use are more than sufficient. The American Academy for the Study of Liver Diseases is currently writing guidelines that should encourage the use of non-invasive methods for liver disease assessment, and I am proud to be part of this worthwhile effort. It is our hope that the publication of guidelines by our professional society will promote non-invasive liver disease assessment by both specialists and nonspecialists.

Expanded application of NILDA, particularly of blood-based assessments of liver fibrosis, would help us triage our patients. Many patients seen at the UPMC Center for Liver Care are found to have steatosis, so the only recommendations after seeing the specialist are lifestyle changes, such as lowering alcohol consumption, losing weight, and eating a healthier diet. Primary care physicians comfortable with ordering and interpreting the blood tests could spare some patients a trip to the liver specialty center. When a blood-based, non-invasive assessment suggests the presence of fibrosis, a referral to a specialty center, such as UPMC Center for Liver Care, should be actively pursued. Our world-renowned hepatologists provide expert care for a full range of liver conditions, with access to cutting-edge treatments for all disorders of the liver and considerable expertise in liver transplant for end-stage disease.

Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006; 43(6): 1317-25.

Altamirano J, Qi Q, Choudhry S, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 5: 31.

Duarte-Rojo A, Heimbach JK, Borja-Cacho D, et al. Usefulness of controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement for the identification of extended-criteria donors and risk-assessment in liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2021.

Qi Q, Weinstock AK, Chupetlovska K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) is a viable alternative to liver biopsy for steatosis quantification in living liver donor transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2021; 35(7): e14339.