Password Reset

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

3 Minutes

Pulmonary Embolism Response Team: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Treat a Complex Disease

by Belinda Rivera-Lebron, MD, MS, FCCP

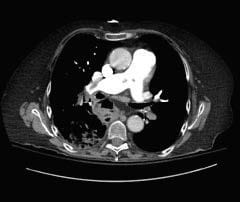

A 64-year-old female presents to the emergency department complaining of one week of cough and increasing dyspnea on exertion. Her symptoms had progressively worsened in 24 hours with associated scant hemoptysis and dull substernal chest pressure. She had a past medical history of a hypertension, hypothyroidism and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism (PE) eight years ago, but had been off anticoagulation for the last six months. On presentation, her vital signs were: temperature 37°C, BP 109/56 mmHg, heart rate 108, respiratory rate 22, oxygen saturation of 92% on room air. Electrocardiogram (EKG) showed sinus tachycardia. Labs were remarkable for a troponin of 0.46 ng/mL (Normal < 0.1 ng/mL). A contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography angiography (CTA) was ordered (see Figure 1), which showed a saddle PE with extension into bilateral pulmonary arteries and an enlarged right ventricle (RV). She was started on a heparin infusion. The Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) was consulted, and the patient was transferred into the intensive care unit (ICU) for closer observation.

Figure 1 (a-d): Contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography angiography (CTA) showing saddle pulmonary embolism (Figure 1 a-c), and enlarged right ventricle (Figure 1d).

On arrival to the ICU, the patient’s vital signs were: temperature 36.1°C, BP 136/76 mmHg, heart rate 140, respiratory rate 34, oxygen saturation of 96% on 4 L nasal canula. On exam, she appeared in mild distress. She had clear lung sounds and no lower extremity edema. A transthoracic echocardiogram was done promptly on arrival (see Figure 2). It showed severe RV enlargement with hypokinesis, interventricular septal flattening, and McConnell’s sign, which refers to a regional pattern of RV free wall dysfunction with sparing of the apex. A multidisciplinary PERT meeting took place between pulmonary and critical care medicine and interventional cardiology. The patient was risk stratified as intermediate-high risk PE with signs of hemodynamic decompensation, based on clinical appearance and increasing heart rate and oxygen saturation. A decision was made to perform catheter-directed thrombolysis, with an initial bolus of 1mg of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) followed by an infusion at 1mg/hr for 12 hours. Heparin infusion was also continued with a low intensity protocol targeting anti-Xa range 0.2-0.5 units/mL. The next morning, her vitals were: temperature 36.5°C, BP 142/82 mmHg, heart rate 98, respiratory rate 18, oxygen saturation of 95% on 1 L nasal canula. Patient appeared more comfortable and reported feeling better. The catheters were removed, and she was transitioned to oral anticoagulation.

Figure 2 (a-b): Transthoracic echocardiogram showing severe right ventricular enlargement and interventricular septal compression.