Password Reset

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

3 Minutes

by Jeremy G. Stone, MD

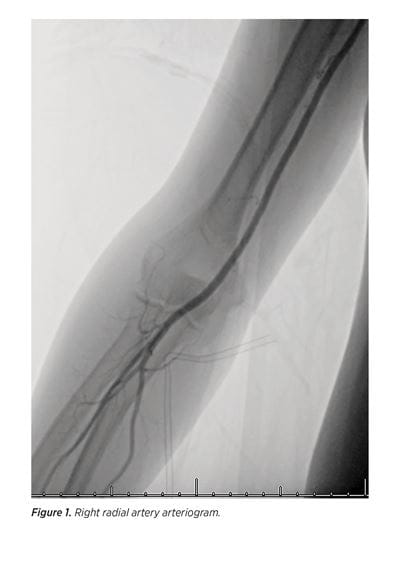

Over the past two decades, interventional cardiology emboldened radial artery access for coronary angiography culminating in a radial-first recommendation by the American Heart Association. This recommendation is due to a preponderance of large, prospective, randomized, multicenter trials showing reduced vascular/bleeding complications, improved patient satisfaction, and even a mortality benefit when radial access is utilized compared to traditional groin/femoral artery access cardiac catheterization.

Neuroendovascular surgery has been slower to adopt radial artery access due to a lack of comparable studies. Overcoming the learning curve of an alternative surgical approach, perceived limitations of accessing a smaller artery, navigating the aortic arch from a different vector, and challenges with regard to changing the culture among the many multidisciplinary staff within the angiography suite

may all dissuade neurointerventionalists who have already mastered the transfemoral approach.

Motivated by a desire to both improve patient satisfaction and push our field forward, our group transitioned over the last year to a radial-artery-first strategy for diagnostic cerebral angiography. Throughout the process of transitioning to radial artery access for neuroendovascular procedures, we prospectively analyzed our success, identified limitations, and published on overcoming the learning curve. Consistent with cardiology data, we found the radial learning curve can be overcome within 30 to 50 cases, and high success can be achieved quickly when approaching the supra-aortic arteries via the right wrist.

With this institutional baseline established, we recently completed a prospective evaluation comprehensively comparing radial and femoral artery access for diagnostic cerebral angiograms. We compared our ability to successfully answer the diagnostic goal of the angiogram, patient safety, procedure times, and patient and staff satisfaction. Notably, we showed equivalent efficacy, radiation dose, contrast agent use, sedating medication use, procedure times, and minor complication rates between the two access approaches. Though procedure times were equivalent, recovery room time was significantly lower in wrist-access patients and discharge home time was faster for our outpatients. Patients overwhelmingly preferred wrist access over groin access with less access site pain, back pain, embarrassment, anxiety, and overall discomfort. Overall patient satisfaction was rated as significantly higher with wrist access compared to groin access.

Within months of transitioning our practice, patients referred for cerebral angiography were coming to the suite requesting wrist access for their procedures. Today, not only can we grant that request, we can confidently do so with the backing of scientific data supporting the safety and efficacy.

Note: Daniel A. Tonetti, MD; Merritt Brown, MD; Ashutosh Jadhav, MD, PhD; Bradley A. Gross, MD; and Benjamin M. Zussman, MD, also contributed to this article.