Password Reset

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

15 Minutes

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are common, with an incidence of 68.6 per 100,000 person-years in the United States. Furthermore, more than 75% of individuals with an ACL injury undergo surgical treatment.1 Surgery is frequently recommended to avoid the development of subsequent meniscal tears, osteoarthritis, and a need for total joint arthroplasty associated with nonoperative management, particularly in young, active patients.2-4 Despite the steady increase in ACL research, questions persist regarding the optimal surgical technique for the treatment of ACL injuries, including the timing of surgery after injury, repair versus reconstruction, graft type, and bundle quantity with anatomic reconstruction.5-7 The purpose of this article is to summarize these current considerations among orthopaedic surgeons to better understand the nature and direction of research and clinical practice surrounding the surgical treatment of ACL injuries.

A landmark study in 1991 showed an increased incidence of knee arthrofibrosis after early ACL reconstruction within one week of injury compared to reconstruction performed within three weeks of injury.8 This led many surgeons to favor delayed reconstruction, as proposed advantages include the opportunity for concomitant injuries to potentially be treated nonoperatively and the opportunity for the injured knee to regain full range of motion (ROM) preoperatively, resulting in an earlier return of full ROM postoperatively.9 Some authors even recommend delaying surgery until two years after an ACL injury to minimize the risk of subsequent graft failure.10,11

However, recent studies have begun to challenge the advantage of delayed ACL reconstruction. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis in which patients were grouped based on surgery performed prior to or after 10 weeks postinjury, no significant differences were found between patient-reported outcomes (PROs) or ROM, though improved Lachman and pivot shift examinations were seen at two and five years postoperatively in the early group when compared to the delayed group in one of three additional studies.12 Additional meta-analyses, with various definitions of early or delayed surgery, have found no clinically significant difference between early and late surgery regarding PROs, complications, ROM, reinjury, or residual laxity.13-15 Therefore, some surgeons are beginning to consider early surgical intervention to be a viable treatment option.

For years, ACL reconstruction involving the use of graft material to create an entirely new ACL has been the gold standard for surgical treatment of ACL tears. ACL repair in which the ACL tear itself is directly repaired (Figure 1) was largely abandoned in the 1990s due to a high incidence of postoperative pain, stiffness, instability, and repair failure in poorly selected patients. However, this approach has begun to make a resurgence.16-19 Proponents argue that ACL repair provides the advantage of a less invasive approach while preserving the native biology, proprioception, and anatomy of the ACL.17,18,20

While results of ACL repair in all patients have unacceptably poor outcomes, there is evidence that early repair of proximal ACL tears within two to four weeks of injury in young patients may result in outcomes similar to ACL reconstruction.21 In addition, internal bracing and biologic augmentation of primary ACL repair have been shown to improve healing as seen on histology and the biomechanical properties of the repaired construct, but these findings have not yet been translated to clinical outcomes.21 Jonkergouw found no significant difference in regards to failure, reoperation rate, or PROs for patients undergoing ACL repair with and without internal bracing in patients with isolated complete proximal ACL tears.17 van der List found that when comparing primary ACL repair with reconstruction, ACL repair resulted in significantly improved early ROM prior to six months, which disappeared at six months.18 However, it is important to note that only patients with proximal ACL tears underwent ACL repair, while patients with midsubstance tears, or with concomitant pathology, received ACL reconstruction. While ACL reconstruction has been the preferred surgical treatment for ACL tears for the last few decades, ACL repair is once again being viewed as a reasonable alternative with several advantages in carefully selected patients.

Another area of much research and debate surrounds the determination of optimal graft type used in ACL reconstruction. ACL grafts are broadly broken down into two main categories: autograft and allograft, with each having a variety of options available. Autograft options include autograft bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB), hamstring tendon (HS), and quadriceps tendon (QT). Allograft options include BPTB, HS, or QT allograft, as well as tibialis anterior or posterior, peroneus longus, or Achilles tendon allograft.

Numerous studies have been performed to compare the various graft types, but no graft option has emerged as the optimal choice. A recent review found no significant difference in graft failure rate among the use of QT, BPTB, or HS autografts in primary ACL reconstructions, while others have shown a decreased rate of failure when using BPTB rather than HS autograft.22-24 In revisions, HS autograft studies have been shown to have a lower rate of complication and reoperation compared to BPTB.25 While Gorschewsky found superior knee function and stability outcomes using BPTB rather than QT with bone block autograft, the majority of studies show QT to be minimally superior or equal to BPTB in regards to postoperative knee laxity, ROM, and PROs.26-28 Likewise, studies comparing QT and HS autografts have shown that QT autograft resulted in minimally superior to equivalent PROs and knee stability.22,29-31 When comparing BPTB and HS autografts, BPTB has been found to be superior in regards to decreased laxity with pivot shift testing and return-to-preinjury activity level.32 In comparing autograft versus allograft, BPTB autograft was found to have a significantly lower rate of revision ACL reconstruction compared to BPTB allograft and has been shown to be superior to various allograft options in young, active patients.33-35 No difference has been shown between the use of HS autograft versus nonirradiated allograft.25 Thus, no clear advantage is seen in knee stability, clinical outcomes, complications, or graft failure among graft types, except for BPTB autograft in young, active patients.

As a result, graft choice is determined by various other factors, such as lack of donor site morbidity or risk of disease transmission with allograft, increased risk of anterior knee pain associated with BPTB autograft, relative decreased hamstring strength seen with HS autograft, or surgeon recommendation.22,27,28,31,32,36 Therefore, while many options exist, no graft choice is clearly superior. Further study is needed to determine the best graft options for patients.

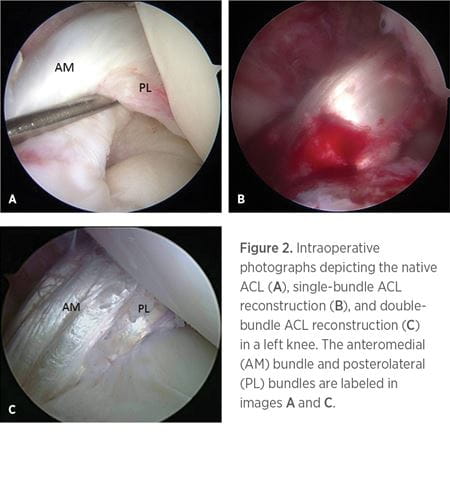

When performing an ACL reconstruction, there is a choice to use a graft consisting of a single-bundle (SB) or double-bundle (DB) (Figure 2). While reconstruction with a DB graft recreates the anatomy of the native ACL, there are instances where the use of a DB graft is impossible, as in cases with a small tibial insertion site, narrow notch, open physes, advanced arthritic changes, and severe bone bruising.37-39 In the majority of studies comparing anatomic SB with anatomic DB ACL reconstruction, DB reconstruction has been found to result in greater knee stability, though improved patient outcomes have not been shown.39-44 Regarding complication or failure rates, meniscal injury, and progression of arthritis, some studies have shown the superiority of DB in comparison to SB reconstruction, although the results are mixed and the quality of data is limited, so additional evidence is needed.41,43,45-47

Closely related to, but distinct from, DB ACL reconstruction is the concept of anatomic ACL reconstruction. Anatomic ACL reconstruction refers to a surgery that functionally restores the ACL to its native dimensions, collagen orientation, and insertion sites.48,49 There has been continued interest in anatomic ACL reconstruction, as technical error is reported as the etiology of the majority of ACL reconstruction failures.50 Anatomic ACL reconstruction has often erroneously been used interchangeably with DB ACL reconstruction; however, the two should not be used interchangeably, as a DB reconstruction can be nonanatomic if the femoral and tibial tunnel sites do not match those of the native ACL.48,51 To assess how anatomic an ACL reconstruction is, a checklist has been created to enable surgeons to evaluate an ACL reconstruction.49 A recent study found an increased incidence in the long-term development of osteoarthritis in patients having undergone a nonanatomic versus anatomic reconstruction based on the score calculated with the use of this checklist.52 Therefore, anatomic reconstruction may be critical in long-term knee function but is

distinct from DB reconstruction.

Much discussion and debate exist as to the best method of surgical treatment for ACL injuries. While surgical timing, ACL repair versus reconstruction, graft type, and bundle number with anatomic reconstruction do not represent every issue currently being addressed, these do represent some of the topics at the forefront of discussion today. Continued research is necessary to uncover the answers to these important questions to determine the best surgical treatment strategies that will lead to the best outcomes for patients.

1 Sanders TL, et al. Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears and Reconstruction: A 21-Year Population-Based Study. Am J Sports Med. 2016; 44(6): 1502-1507.

2 Mok YR, et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Performed Within 12 Months of the Index Injury Is Associated With a Lower Rate of Medial Meniscus Tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019; 27(1): 117-123.

3 Sanders TL, et al. Long-term Follow-up of Isolated ACL Tears Treated Without Ligament Reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017; 25(2): 493-500.

4 Shea KG, Carey JL. Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Evidence-Based Guideline. JAAOS. 2015; 23(5): e1-e5.

5 Kim HS, Seon JK, Jo AR. Current Trends in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2013; 25(4): 165-173.

6 Paschos NK, Howell SM. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Principles of Treatment. EFORT Open Rev. 2016; 1(11): 398-408.

7 Kambhampati SBS, Vaishya R. Trends in Publications on the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Over the Past 40 Years on PubMed. Ortho J Sports Med. 2019; 7(7): p. 2325967119856883.

8 Shelbourne KD, et al. Arthrofibrosis in Acute Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: The Effect of Timing of Reconstruction and Rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med. 1991; 19(4): 332-336.

9 Shelbourne KD, Patel DV. Timing of Surgery in Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Injured Knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1995; 3(3): 148-156.

10 Nagelli CV, Hewett TE. Should Return to Sport Be Delayed Until 2 Years After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction? Biological and Functional Considerations. Sports Med. 2017; 47(2): 221-232.

11 Paterno MV, et al. Incidence of Second ACL Injuries 2 Years After Primary ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport. Am J Sports Med. 2014; 42(7): 1567-1573.

12 Lee YS, et al. Effect of the Timing of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction on Clinical and Stability Outcomes: A Systematic Review

and Meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2018; 34(2): 592-602.

13 Deabate L, et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Within 3 Weeks Does Not Increase Stiffness and Complications Compared With Delayed Reconstruction: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Sports Med. 2019 Aug 5: 0363546519862294.

14 Ferguson D, et al. Early or Delayed Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Is One Superior? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2019; 29(6): 1277-1289.

15 Manandhar RR, et al. Functional Outcome of an Early Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Comparison to Delayed: Are We Waiting in Vain? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018; 9(2): 163-166.

16 van Eck CF, Limpisvasti O, ElAttrache NS. Is There a Role for Internal Bracing and Repair of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament? A Systematic Literature Review. Am J Sports Med. 2017; 46(9): 2291-2298.

17 Jonkergouw A, van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Arthroscopic Primary Repair of Proximal Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears: Outcomes of the First 56 Consecutive Patients and the Role of Additional Internal Bracing. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019; 27(1): 21-28.

18 van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Range of Motion and Complications Following Primary Repair Versus Reconstruction of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament. Knee. 2017; 24(4): 798-807.

19 Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Primary Repair of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament: A Review of Recent Literature (2016-2017). Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2019; 7(3): 297-300.

20 Gipsman AM, Trasolini N, Hatch GFR 3rd. Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Single-Bundle Repair With Augmentation for a Partial Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear. Arthrosc Tech. 2018; 7(4): e367-e372.

21 Taylor SA, et al. Primary Repair of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2015; 31(11): 2233-2247.

22 Mouarbes D, et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Outcomes for Quadriceps Tendon Autograft Versus Bone–Patellar Tendon–Bone and Hamstring-Tendon Autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2019 Dec; 47(14): 3531-3540.

23 Samuelsen BT, et al. Hamstring Autograft Versus Patellar Tendon Autograft for ACL Reconstruction: Is There a Difference in Graft Failure

Rate? A Meta-analysis of 47,613 Patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017; 475(10): 2459-2468.

24 Laboute E, et al. Graft Failure Is More Frequent After Hamstring Than Patellar Tendon Autograft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018; 26(12): 3537-3546.

25 Grassi A, et al. Does the Type of Graft Affect the Outcome of Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction? A Meta-Analysis of 32 Studies. Bone Joint J. 2017; 99-b(6): 714-723.

26 Gorschewsky O, et al. Clinical Comparison of the Autologous Quadriceps Tendon (BQT) and the Autologous Patella Tendon (BPTB) for the Reconstruction of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007; 15: 1284.

27 Han HS, et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Quadriceps Versus Patellar Autograft. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008; 466: 198-204.

28 Lund B, et al. Is Quadriceps Tendon a Better Graft Choice Than Patellar Tendon? A Prospective Randomized Study. J Arthroscopic Rel Surg. 2014; 30(5): 593-598.

29 Cavaignac E, et al. Is Quadriceps Tendon Autograft a Better Choice Than Hamstring Autograft for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction?

A Comparative Study With a Mean Follow-up of 3.6 Years. Am J Sports Med. 2017. 45(6): 1326-1332.

30 Runer A, et al. There Is No Difference Between Quadriceps‑ and Hamstring-Tendon Autografts in Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction:

A 2‑Year Patient‑Reported Outcome Study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018; 26: 605-614.

31 Lee JK, Lee S, Lee MC. Outcomes of Anatomic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Bone–Quadriceps Tendon Graft Versus Double-Bundle Hamstring Tendon Graft. Am J Sports Med. 2016; 44(9): 2323-2329.

32 Xie X, et al. A Meta-Analysis of Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Autograft Versus Four-Strand Hamstring Tendon Autograft for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Knee. 2015; 22(2): 100-10.

33 Kane PW, et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Autograft Versus Allograft in Skeletally Mature Patients Aged 25 Years or Younger. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016; 24(11): 3627-3633.

34 Steadman JR, et al. Patient-Centered Outcomes and Revision Rate in Patients Undergoing ACL Reconstruction Using Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Autograft Compared With Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Allograft: A Matched Case-Control Study. Arthroscopy. 2015; 31(12): 2320-6.

35 Kaeding CC, et al. Risk Factors and Predictors of Subsequent ACL Injury in Either Knee After ACL Reconstruction: Prospective Analysis of 2488 Primary ACL Reconstructions From the MOON Cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2015. 43(7): 1583-1590.

36 Fisher F, et al. Higher Hamstring‑to‑Quadriceps Isokinetic Strength Ratio During the First Post‑Operative Months in Patients With Quadriceps Tendon Compared to Hamstring Tendon Graft Following ACL Reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018; 26: 418-425.

37 Salminen M, et al. Choosing a Graft for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Surgeon Influence Reigns Supreme. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2016; 45(4): E192-7.

38 Hensler D, et al. Anatomic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Utilizing the Double-Bundle Technique. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012; 42(3): 184-95.

39 Murawski CD, et al. Operative Treatment of Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture in Adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014; 96(8): 685-94.

40 Hussein M, et al. Prospective Randomized Clinical Evaluation of Conventional Single-Bundle, Anatomic Single-Bundle, and Anatomic Double-Bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: 281 Cases With 3- to 5-Year Follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011; 40(3): 512-520.

41 Mascarenhas R, et al. Does Double-Bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Improve Postoperative Knee Stability Compared With Single-Bundle Techniques? A Systematic Review of Overlapping Meta-analyses. Arthroscopy. 2015; 31(6): 1185-96.

42 Xu M, et al. Outcomes of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Using Single-Bundle Versus Double-Bundle Technique: Meta-Analysis of 19 Randomized Controlled Trials. Arthroscopy. 2013; 29(2): 357-65.

43 Tiamklang T, et al. Double-bundle Versus Single-Bundle Reconstruction for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 11: Cd008413.

44 van Eck CF, et al. Single-bundle Versus Double-Bundle Reconstruction for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture: A Meta-Analysis — Does Anatomy Matter? Arthroscopy. 2012; 28(3): 405-24.

45 Zhu Y, et al. Double-Bundle Reconstruction Results in Superior Clinical Outcome Than Single-Bundle Reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013; 21(5): 1085-1096.

46 Sun R, et al. Prospective Randomized Comparison of Knee Stability and Joint Degeneration for Double- and Single-Bundle ACL Reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015; 23(4): 1171-1178.

47 Chen H, et al. Single-bundle Versus Double-bundle Autologous Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials at 5-Year Minimum Follow-up. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018; 13(1): 50.

48 van Eck CF, et al. “Anatomic” Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of Surgical Techniques and Reporting of Surgical Data. J Arthroscopic Rel Surg. 2010; 26(9, Supplement): S2-S12.

49 van Eck CF, et al. Evidence to Support the Interpretation and Use of the Anatomic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Checklist. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013; 95(20): e153.

50 van Eck CF, et al. The Anatomic Approach to Primary, Revision and Augmentation Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010; 18(9): 1154-63.

51 Karlsson J, et al. Anatomic Single- and Double-Bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction, Part 2: Clinical Application of Surgical Technique. Am J Sports Med. 2011; 39(9): 2016-26.

52 Rothrauff BB, et al. Anatomic ACL Reconstruction Reduces Risk of Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review With Minimum 10-Year Follow-Up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019; Epub ahead of print.